Part 1: Prepping the bark

Part 2: Building the terrain

Part 3: Painting & Finishing

Required materials:

- Paints (duh)

- Brushes

- Water cup

- Paper towels or rags

- Large tub/“flock box”

- Flock

- Other finishing materials (Super Turf, Buffalo Tufts, etc.)

- Tootbrush or wire brush (optional)

- White glue or tacky glue

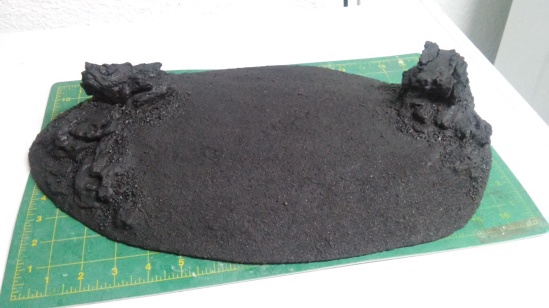

What you essentially have now is a fully-constructed, primed miniature that’s ready for painting.

A recap of everything that’s happened up to this point, in photo form. Does this look familiar?

Keeping with the miniature analogy for a moment, the time required for each step of the process of making hills is kind of the inverse of how miniature painting goes. With miniatures, while it does take some time to properly clean and prep a miniature, the vast majority of the time is spent on the actual painting (when doing a high-quality paint job, anyway). By contrast, the bulk of the time required for creating a hill is spent on the “prep work” phase getting it to where we are now. Implication: Most of the work is done by this point, and we’re going to see some dramatic results in a short period of time!

Step 1 – Choose your colors

The type of hill you’re creating will help inform your color choices, not only for your paint, but also for the flock and other foliage you use (if any). For example, if you’re making gently rolling hills (like the one in this tutorial), the colors and amount of foliage you use will be different than if you’re creating craggy hills and spires for a barren wasteland. So in reality, your color choices are hopefully something you’ve been thinking about since you first started cleaning sycamore bark.

The Rule of CoolTM reigns supreme when making terrain; how cool the terrain looks is more important than how realistic it looks. Of course, there’s some interaction between coolness and realism, as part of what makes something look cool is that it looks realistic. But as a rule of thumb, if it comes down to a choice between making something look cool or making it look realistic, I usually go with cool.*

Another point that I keep in mind when creating various types of terrain is that even in the real world, there is a nearly endless amount of variety in the different landscapes that exist. Spend a few minutes searching images online and you’ll see what I mean. When you throw fantasy and sci-fi alien worlds into the mix, the possibilities literally become endless. So, focus on what looks good, and don’t worry as much about realism.

The best practical tip for choosing colors is to remember that objects appear darker the further away you are from them. In the case of miniature wargaming, standing at a normal viewing distance of a few feet away can be enough to make terrain look slightly darker than when you look at it up-close.

For my rolling hills, I’m going to start with a dark reddish-brown over everything. This will provide a good base for the additional colors I’m going to paint over the rocks, as well as for the “soil” for the flock and other foliage.

Step 2 – Paint the terrain

Drybrushing is the main technique I’ll be using for painting this hill. I’m assuming you’re already familiar with how to drybrush considering that most people in this hobby start with painting miniatures before branching out into making terrain, but for those of you who are not (again, not sure how you got here, but welcome!), I’ll explain. To drybrush, put a small amount of paint on the tip of your brush. Wipe the excess onto a rag or paper towel until the paint that’s left on the brush is very pigment-heavy and feels nearly dry (hence the name). Now, lightly wipe paint onto the terrain using a gentle dusting motion. The pigments will come off onto the raised surfaces of the terrain, effectively highlighting it. You will have to reload and wipe your brush numerous times to paint an entire piece of terrain. Drybrushing is best done slowly and not something to be rushed; the more brushstrokes you use, the more subtle and less chalky the results will be. You’ll get a literal feel for how this works with a little practice.

Conventional miniature-painting wisdom says that drybrushing destroys brushes and for this reason, you want to use cheap brushes. Drybrushing does wear out brushes, but in this case, a worn-out brush won’t have a deleterious effect on your ability to paint terrain. What will have a deleterious effect on your ability to paint is the cramping pain in your hand you’ll get from using a poor-quality brush (looking at you, chip brushes!). Spend a little extra money for a brush that has a comfortable handle. And by “a little extra” I mean $6-$7 for a 2-inch hobby brush with a round ergonomic handle, not a $200 W&N Series 7. If you’re really serious about terrain-making, you can buy something like the brushes in the photo below.

These brushes are my go-to brushes for drybrushing terrain. I have a few other brushes that I use sometimes, but these are my favorites. For you miniature painters out there, the two on the left are labeled as a size 50.

Bristle stiffness can vary. Generally, stiffer bristles work better, but supple brushes have their use as well. Over time, you’ll probably build up a selection of brushes in different shapes, sizes, and stiffness as you experiment with new brushes and learn how you can use them to get particular effects. In addition to different brushes, you should also experiment with different amounts of pressure and the amount of paint on the brush to see what types of effects these variations produce.

For this hill, I didn’t use anything else on the soil besides the reddish-brown, but I used several brownish-grays on the rocky areas. Just like with painting miniatures, in general, the more layers you use, the better the paintjob will look. Drybrush each of your chosen colors onto your terrain.

If you refrain from washing your brush in between switching colors, this will help subsequent layers blend together better. However, you may find that you will have to rinse your brush brush before you’re finished painting as the built-up paint may dry out and make your brush too stiff to drybrush with. If you have to rinse your brush, make sure to squeeze as much water out of it as possible or just switch to a different brush because using a damp brush will wreak havoc on your attempts to drybrush.

If you look closely, you can see that I used two different color schemes on the rock formation, light brownish-grey on the left, light grey on the right. I’m a tricky bastage, ain’t I? After deciding which one I like better, I’ll repaint the other one to match. Note also the subtle, but definite, change in color of the soil from the previous picture.

Step 3 – Flock

It won’t be long until the hill is finished. There are numerous companies that make flock, and the sheer variety of colors and levels of coarseness quite large. An important tip here is to buy products that come in quantities intended for use with railroad scenery and dioramas, not for basing miniatures. Basing material is the exact same thing, but sold at a much higher price point.

Flock comes in single colors that you can mix together to make custom blends, but if you’re new to using it, I recommend using a pre-mixed blend. Heck, I still prefer starting with blends and doing a little color customization if I feel like it because they’re so convenient to use! Besides color, you also have to decide how much to use. Is your terrain depicting a lush valley or an arid desert? In this particular case, I’m going to use quite a bit of flock as ground cover.

The process is very similar to applying the first layer of sand, even down to using a sand box (“flock box” in this case, I suppose). If you have the space and a few extra dollars, I strongly recommend having separate tubs for sand and flock. Having them ready to go when you need them without having to rinse them out in order to switch from one material to another is quite handy. To recap: 50/50 white glue/water mixture (use a cheap brush for application), work in manageable sections, sprinkle on flock, shake off excess, let dry. The key difference with flock, however, is that rather than coating the entire surface of the hill, in this case, I’m intentionally leaving some bare patches of soil showing through, as this is usually more interesting than a solid green carpet (although feel free to go solid green if that’s what you prefer). I’m also gluing some flock onto the rocks.

Note that the bare batches peeking through are deliberate.

Once the base ground cover is dry, go back and add in some highlight colors, as this adds greater depth and visual interest. For this piece, I’ve simply used a brighter green blend, liberally applied. Try to be somewhat random in how you apply the flock. I’m also being careful to still leave a little bit of bare soil showing. Randomness is especially important for the highlight colors; put different amounts in different locations. You can also experiment with using a dry stencil brush, toothbrush, or wire brush to create more bare patches, although I haven’t done that with this piece. Just be mindful that you don’t scrub too hard if you try this or you can end up scrubbing all the way down to the foam!

Looking good, if I do say so myself. We could stop here and call it finished, but we’re going to do some more work to really put it over the top.

Once everything is dry, give the whole thing a generous spray with a diluted white glue/water mix (1:3 to 1:4). This is especially important because flock has a tendency to come off if not glued down sufficiently. After spraying, wait for it to dry again while you read about the next step.

Step 4 – Accents

We’re almost there. To make this piece really pop, we’re going to add some extra foliage in a few different colors. Again, like flock, there are myriad options out there, almost to the point of being overwhelming. Two materials I really like using are Super Turf and Buffalo Tufts. Super Turf has a really neat physical structure that makes it look great both in small amounts or large clumps. Buffalo Tufts are perfect for simulating patches of longer grass or weeds and look awesome with minimal work.

Super Turf can be applied by hand, but it’s easier to use tweezers to pull Buffalo Tufts from their adhesive sheet and apply them where you want them. Use dabs of white or tacky glue to attach them to your hill. It’s helpful to apply 50/50 white glue/water to the Super Turf after you place it, but use a dropper bottle of some sort (an empty white glue bottle works well for this) instead of spraying the entire piece again because the 50/50 is unnecessary for the Buffalo Tufts and can even affect how the strands splay out.

PRO TIP(TM): When adding accents, remember, you’re adding accents. Less is more. Just like with salt, pepper, parsley, rosemary, and LSD, you don’t want the supporting flavors to overpower the main dish. The right amount of accents will fit perfectly with your terrain and enhance the overall effect/realism/coolness. Too much, and it’ll just look obnoxious and noobish. Also, accents should be random, but don’t try too hard to be random; it sounds like kind of a zen thing, but don’t be random, just be. Random placement of accents is crucial to kicking the overall effect up a notch, but it’s actually one of the trickiest things to do properly. Learn to let go, don’t think about it too hard, and just let the terrain guide you. (Whoa, I wasn’t kidding about going easy on the LSD.)

Congrats on finishing your hill! You now have a terrain piece that you can be proud to display and game with. It’ll take a while to make enough terrain to cover an entire table, but the techniques shown here produce durable pieces that should last for a long time with some common-sense care (in other words, don’t use your terrain as a foot stool when you can’t reach the top shelf in the cabinet).

You can alter the techniques shown here in almost any number of ways. Online photos provide a limitless source of inspiration. If you can imagine it, chances are that something like it exists somewhere in the world. Experiment with different shapes and sizes of hills. Use different materials, such as pine bark and lava rock. Make towering cliffs or plateaus. Make spires. Experiment with different types and colors of flock. Make some alien-themed pieces and paint them purple.

If you’d like to make some of the early parts of the terrain-making process a little easier, or even just buy terrain that’s ready to go without requiring any work on your part, I know a place where you can get some:

https://www.etsy.com/shop/Terrainify

Happy gaming!

* Incidentally, this is also the same decision-making process used by female members of the human species of child-bearing age when trying to choose between potential sexual partners. Think about it. Who do chicks dig more: the buttoned-down, responsible guy with a boring, yet stable job, or the bad boy rebel with wild hair and motorcycle who exudes “devil may care” charm?

Gents, the upshot of this is that if you learn how to make cool terrain, you will be cool, and thus, you will be a hit with the ladies. (Hey, it worked for me. Or did it work in spite of my terrain-making and other geeky interests? Nah…) Ladies, possessing mad terrain-making skillz is a worthwhile investment for you as well, but will be superfluous for attracting a potential mate; in the right environment, the ontological fact of your being female will be enough to provide you with a plethora of viable, eager reproductive partners. And by “right environment,” I mean your stereotypical basement-dwelling cadre of gamers or FLGS patrons.

However, in recent years, there has been anecdotal evidence of an upward trend of gamers as an aggregate becoming more socially competent and, dare I say, hygienic. Not to mention an increase in the number of basement dwellers and FLGS patrons who are also female. Meaning that you may eventually have to up your game (no pun intended). So, on second thought, ladies, study these tutorials and learn how to make kick-ass terrain in order to gain you a competitive advantage over those non-terrain-making strumpets!